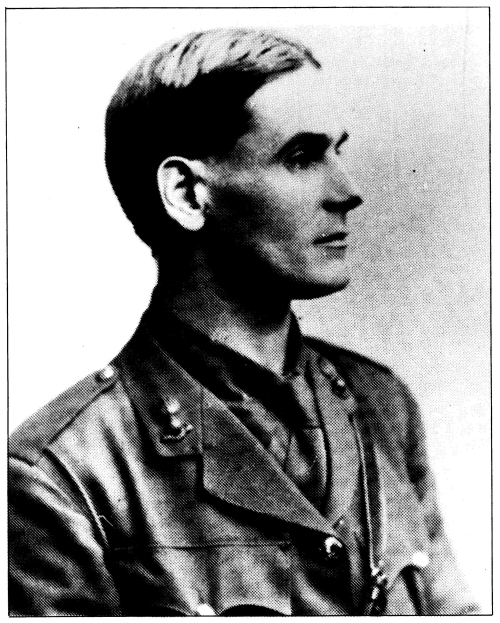

A nice profile shot of WHH in uniform. Likely around 1916 or so.

Today, April 19th, marks 100 years since the death of William Hope Hodgson.

By 1918, World War I (“The Great War”) had been raging for nearly four years since its beginning in July, 1914. When the war finally ended in November, 1918, the world had been changed. The European map had to be redrawn with the destruction of four Empires. An estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilians (including victims of several genocides not the least of which was the attempted extermination of the entire Armenian population by the Ottoman Empire) died as a result of the conflict. Many of the casualties were results of the increased technological and industrial advances which made new methods of war such as chemical warfare possible.

The Great War effectively eliminated almost an entire generation of young men and also had a powerful impact on the world of art and literature. The war claimed the lives of Wilfred Owen (poet), Alain-Fournier (novelist), August Macke (painter), H. H. Munro (writer) and many others.

In the 1989 collection, The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets and Playwrights, Tim Cross presents a list of approximately 750 names while commenting that “a complete list of all poets, playwrights, writers, artists, architects and composers who died as a result of the First World War is an impossible task”.

William Hope Hodgson is a part of that long, sad list.

When war broke out in 1914, Hodgson was still living in France with his wife, Bessie. They had been married for only a few months more than a year. Hodgson, with typical patriotic fever, rushes back to England to enlist while sending his wife back to live with his mother and sister in Borth.

In July of 1915, Hodgson is commissioned as a Lieutenant in the 171st Battery of the Royal Field Artillery. He adamantly refuses to join the Royal Navy despite his more than ample qualifications for sea duty. (It has been noted by many that this is indeed ironic because, had Hodgson joined the Royal Navy, he would have had a far greater chance of surviving the war.)

Shortly under a year later, in June of 1916, Hodgson is thrown from a horse and suffers a broken jaw and major concussion and is sent home to recover. R. Alain Everts makes the contention that this injury will follow Hodgson for the rest of his brief life.

No doubt his Commanding Officer and division had thought that the injury would have been enough to end Hodgson’s participation in the war but, true to form, Hodgson refused to accept the limitations of his body. Relying on his knowledge of physical culture, Hodgson pushes himself back to health and re-enlists. This time he is assigned to the 84th Battery and sent to France in October of 1917.

At this point, he has less than six months to live.

During the spring of 1918, the 84th Battery participates in a series of battles and is part of the efforts to turn back the German army’s push.

Everts recounts Hodgson’s final days:

On 12 March, 1918 the Brigade took over positions at Brombeck, and on 20 March, sustained heavy gas shelling and high velocity shelling at the Tourelle Crossroads nearby. On 30 March, they were relieved by Belgian Artillery, and on 2 April the Battery marched to the Ploegsteert area to relieve Australian Artillery. This was to be the scene of the final act of Hodgson’s valiant life.

The Battery took a position at Le Touquet Berthe. The Front was quite silent for a time—and for the first time there were no casualties in action. On 9 March the Germans attacked south of the Armentieres and penetrated allied lines for some distance and forced the British to move further north from Steenbeke. On the dawn of the following day, the Battery had undergone heavy night shelling and all communications were cut. The Germans advanced and the front section of the Battery had to retreat, leaving behind their guns, which they blew up. The Germans circled behind Hope’s Battery and approached to within 200 yards forcing the whole detachment to fall back.

On the day of 10 April 1918, the Germans launched a big attack, and apparently this put Hodgson in hospital briefly. On the night of 16 April the Battery withdrew, and a Forward Observation Post was set up. The man who volunteered for the Forward Observing Office the next day—17 April—on Mont Kemmel, was none other than W. Hope Hodgson. The details surrounding the tragic death of Hope can now be clarified after nearly 55 years—and in clarifying them some errors regarding his death have been corrected. His Commanding Officer filled in the details—on Thursday, 18 April, he sent Hodgson with another N.C.O. on Forward Observation. On 19 April, Hope was heard from once and then there was silence from him for the remainder of the day. That day, 19 April, William Hope Hodgson was reported missing in action to his C.O. The following day, under continuous fire, the C.O. went to check himself to determine the fate of his F.O.O.’s. He eventually found a French officer who showed him a helmet with the name Lt. W. Hope Hodgson on it—and reported that a British Artillery Officer and a Signaler had suffered a direct hit by a German artillery shell on 19 April and had both been blown nearly completely apart. What little remained was buried on the spot—at the foot of the eastern slope of Mont Kemmel in Belgium. During this period, the C.O. was under continuous fire, and upon his return to base, he confirmed the death of Lt. W. Hope Hodgson, and it was entered on 23 April.1

Photo of German artillery barrage at Ypres.

Hodgson’s Commanding Officer wired the heart-breaking news to Hodgson’s mother and wrote:

“I cannot express my deep sympathy for you in your great bereavement. I feel it most terribly myself, and so do all the other officers and men of the battery. He was the life and soul of the mess—always so willing and cherry. Of his courage I can give no praise that is high enough. He was always volunteering for any dangerous duty, and it was owing to his entire lack of fear that he probably met his death on April 17. He had performed wonders of gallantry only a few days before, and it is a miracle that he survived that day. I myself am deeply grieved, having lost a real, true friend and a splendid officer.”2

Hodgson’s obituary appeared in newspapers around the world, signifying his stature in the writing world. Of these many notices, The Times is perhaps the most poignant:

Second Lieutenant W. Hope Hodgson, RFA, killed in action on April 17, was the second son of the late Rev. Samuel Hodgson, and the author of “The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’”, “The Night Land”, “Men of the Deep Waters” and other books. His early days were spent in the merchant service, where he gathered his material for many of his thrilling sea stories. He was a notable athlete, a fine boxer, a strong swimmer, and an all-round good sportsman. He was awarded the Royal Humane Society’s medal for saving life at sea. At the outbreak of the war Lieutenant Hodgson was living in Sanary, on the south coast of France. He returned to England, joined the University of London Officer Training Corps. and got his commission in the RFA in 1915. As the result of a serious accident in camp, he was gazetted out of the Army in 1916; but he never rested until he passed the medical board as fit, and obtained another commission in March 1917, in the RFA. He saw much active service round Ypres during last October.3

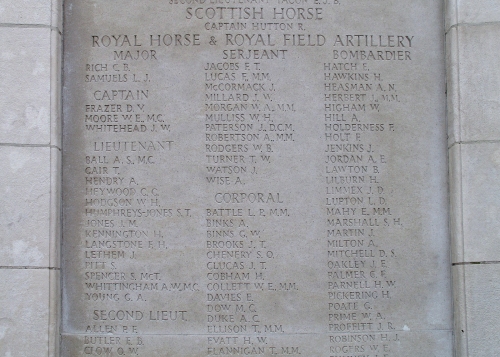

There was nothing left of Hodgson’s body to send home. This was not an uncommon experience in war. Many soldiers died in foreign lands with nothing left to send back home to their grieving families. What often takes their place are memorial cemeteries that honor those who had fallen. There is one such cemetery in Belgium. At Tyne Cot Cemetery, William Hope Hodgson’s name is engraved.

Like many casualties of war, we are left to wonder what Hodgson could have accomplished if he had not died so tragically young. It seems almost certain that Hodgson would have returned to writing as a source of income. At the time of his death, Hodgson had been concentrating more on adventure stories and serial characters. It had been years since he had written a novel but there is a chance that his experiences could have inspired him back to that form.

Although we have very little in terms of letters from Hodgson, we do have this excerpt courtesy of Sam Moskowitz where Hodgson writes to his mother:

“The sun was pretty low as I came back, and far off across that desolation, here and there they showed–just formless, squarish, cornerless masses erected by man against the infernal Storm that sweeps for ever, night and day, day and night, across that most atrocious Plain of Destruction. My God! talk about a Lost World–talk about the end of the World; talk about the ‘Night Land’–it is all here, not more than two hundred odd miles from where you sit infinitely remote. And the infinite, monstrous, dreadful pathos of the things one sees–the great shell-hole with over thirty crosses sticking in it; some just up out of the water–and the dead below them, submerged….If I live and come somehow out of this (and certainly, please God, I shall and hope to), what a book I shall write if my old ‘ability’ with the pen has not forsaken me.”4

One hundred years ago today, William Hope Hodgson walked his own path to that ‘Plain of Destruction’, never to come out again.

William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918)

Notes:

1. Everts, R. Alain. Some Facts in the Case of William Hope Hodgson: Master of Fantasy. Soft Books, 1987.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Moskowitz, Sam. Out of the Storm: Uncollected Fantasies by William Hope Hodgson. Donald M. Grant, 1973.

Thank you so much for this well-spoken piece. That small bit from WHH’s letter is one of the most vivid condemnations of war I have read. Most here a century later are only dimly aware of the yawning Darkness that was that Great War, and its lingering impact on all that we are. . WHH as a man and a writer is one of many perfect and tragic icons of that lasting horror.

Good piece! Thanks.